|

(The Kathryn Tucker Windham blog is written by her daughter, Dilcy Windham Hilley.)

My mother loved cemeteries. As children, we never questioned why Mother would pull the car into a country cemetery just to roam about and read the tombstones. It was part of the journey, a part I learned to love, too, as I got older and wandered through graveyards with my mother. One of our favorite epitaphs was on a headstone in southwest Alabama. It read simply: She did what she could. Mother and I often teased each other with that phrase when outcomes were disappointing Mother had a long-standing tradition of taking her guests on picnics to Old Live Oak Cemetery in Selma. It is a remarkable resting place, with curtains of Spanish moss draping the oak trees and a coolness that even the river city heat can’t dispel. Mother would pack pimento cheese sandwiches, potato salad, and Little Debbie Cakes in a cooler, pour up a jug of tea, and grab a quilt to use as a tablecloth. Being a believer in recycling, she would take along Tide detergent measuring cups to hold the potato salad servings. Pretense was never a word associated with my mother. Then she and her guests would select a family to dine with and spread the quilt along the raised brick walls of that family’s plot. And have a picnic. It was her signature entertainment, and dozens of friends and acquaintances enjoyed it through the years.

8 Comments

(Unless otherwise noted, the Kathryn Tucker Windham blog is written by her daughter, Dilcy Windham Hilley.)

My mother was fascinated with the English language. She loved words---their sounds, their usage, their meanings. One words she was especially fixated on was grits. Mother regularly preached that grits is a singular noun. “This grits is hot.” “This grits is good.” She insisted that grits never “are.” She said, though it may sound peculiar to the ear, it is nonetheless correct, much like, “This corn is frozen,” or, “This okra is breaded just right.” In Mother’s book, this was not a grammatical misstep. It was proper. Mother took her “grits is” mission so far as to write the late syndicated columnist, James Kilpatrick, who had a weekly column called “The Writer’s Art” that ran in newspapers across the country. Mother pled her case for her cause, and Kilpatrick led one of his columns with her letter, proving to his audience the passion people have for English usage. I do recall he took neither side of the debate. Grits can be an ordinary dish, or it can be impressively fancified. Waffle House grits is one thing, but the spell they put on grits at Birmingham’s Highlands Bar and Grill is quite another. No matter the form in which it’s served, bear in mind that it once was one woman’s quest to rid the world of the improper practice of pluralizing grits. (Unless otherwise noted, the Kathryn Tucker Windham blog is written by her daughter, Dilcy Windham Hilley.)

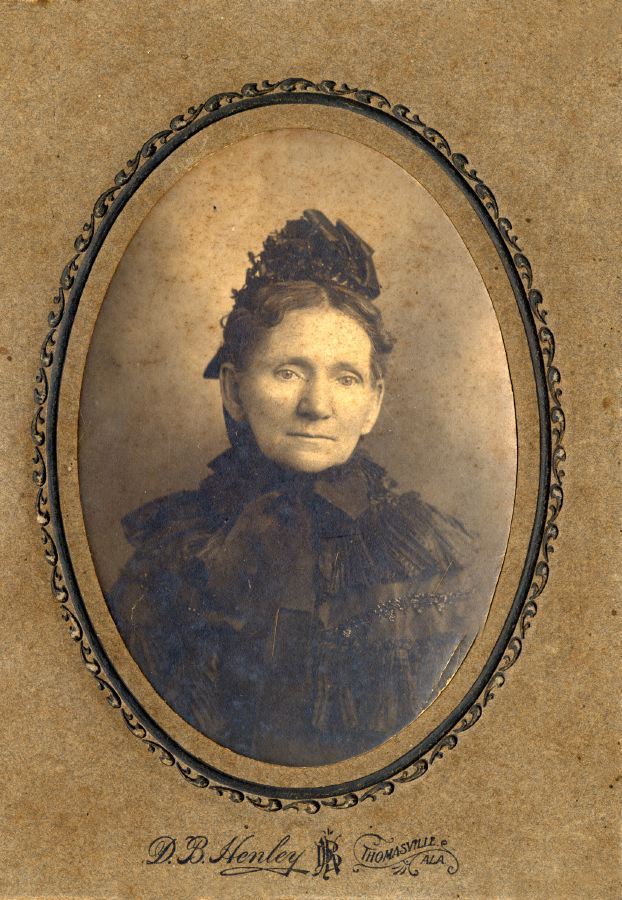

My great aunt, Bettie Larkin Forster, had enormous ears. All the women on the Tucker side of the family did really, and some of us still do. Mother always said big ears are the sign of a generous person. Aunt Bet must have been magnanimous. Everybody in Thomasville loved my Aunt Bet. She was the town’s postmaster for decades, as was her mother before her. She refused to allow anyone to call her a postmistress---said she was nobody’s mistress at all. After she retired from the Thomasville Post Office and was into her eighties, Aunt Bet had a fall and broke her hip. She was bedridden thereafter until her death at 94. I didn’t know Aunt Bet until she was confined to bed, and, for reasons only a child can concoct, I was terrified of her. No one understood my fear, least of all my mother. I would beg not to be left alone in the room with this dear, sweet, horrifying woman who was my great aunt. “Behave yourself,” Mother would admonish. “Go in the room and give Aunt Bet a hug.” And I’d schlep myself up to her bedside, growing anxious and weak in the knees as the air around me filled with lavender dusting powder and crippleness. Aunt Bet entertained herself from her bed by ordering from catalogs, not for any particular occasion, primarily just to pass the time. When the family suggested she had acquired a more-than-adequate amount of stuff, Aunt Bet would have her nurse, Heatha, hide the packages beneath her high spool bed. When she died, the family found enough wedding, anniversary, birthday, and Christmas gifts to last for years. Aunt Bet died before I outgrew my fear of her. I wish I had known her better. When I got older, Mother told me my great aunt kept a running record of gentlemen who had come to visit her. I also learned Aunt Bet, in her mobile years, made divine muscadine wine---even on Sundays. And her exquisite wedding cakes were desired throughout southwest Alabama. Yes, I wish I’d known her better. Like my mother did, I would have adored her. (Unless otherwise noted, the stories about Kathryn Tucker Windham are written by her daughter, Dilcy Windham Hilley.)

As Mother progressed into her 80s, it was necessary to see her doctor more frequently. It’s a distressing fact of life that, as we age, we often see more of our doctors than we do of our family. Selma’s Dr. Boyd Bailey spent more than a decade taking excellent care of my mother in her later years. He repaired broken bones, compressed varicose veins, prescribed diuretic drugs, and generally kept Mother assembled until she departed this life. One day, during what must have been a rough patch in her generally healthy life, Mother had an appointment with Dr. Bailey. When he called her in, she told him with some discouragement that her years were getting the better of her, that she was feeling old. “Nonsense, Miss Kathryn!” Dr. Bailey replied. “You’re simply on the outer fringes of middle age!” Let us all take that to heart. (Unless otherwise noted, the Kathryn Tucker Windham blog is written by her daughter, Dilcy Windham Hilley.)

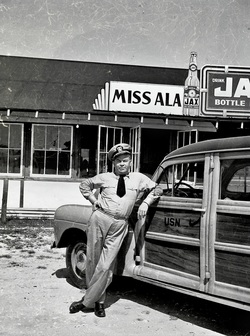

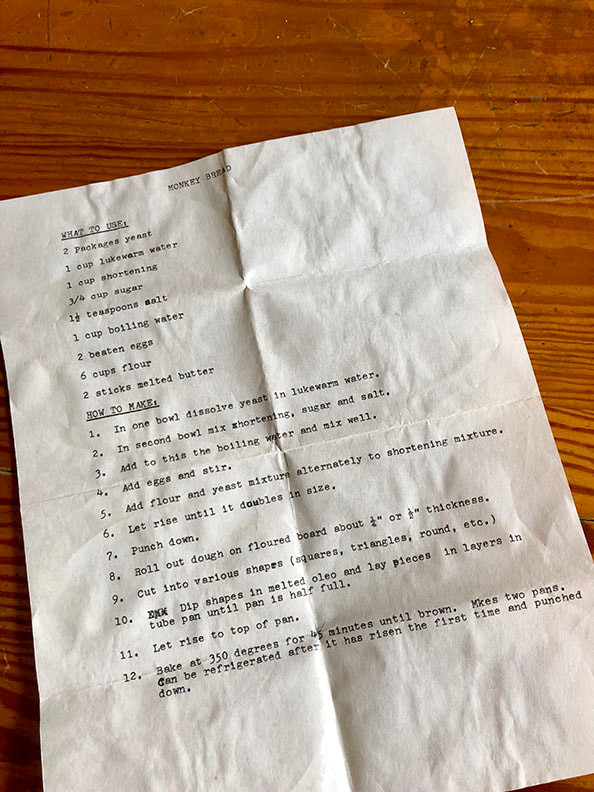

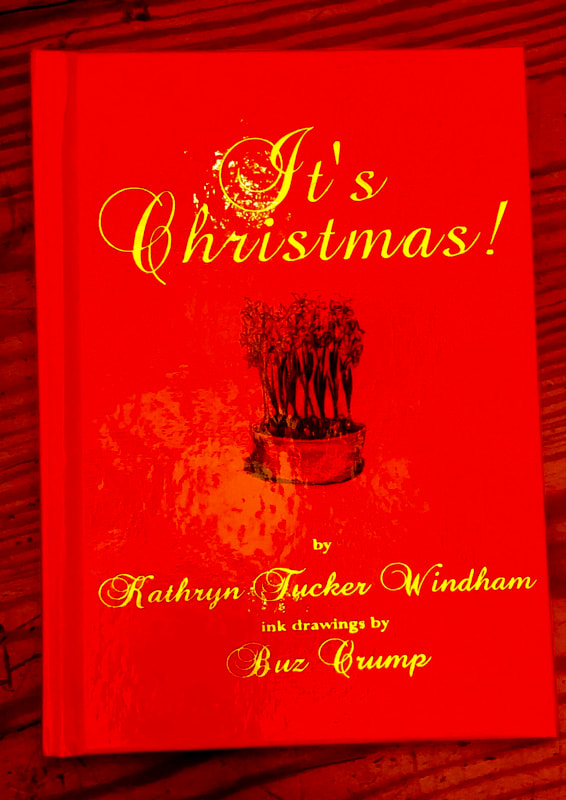

My mother was a good cook but not the fancy gourmet kind. She once told me that if you could cook one thing well, people would assume you were a good cook. Once Mother graduated Huntingdon College and was out on her own, she learned to cook scrambled eggs well. I’m not sure how long you can get by with serving scrambled eggs repeatedly, but that was her claim to being a good cook. Of course, she eventually learned to cook other dishes and even wrote several cookbooks. I don’t recall her testing out many of the recipes on us children. As a matter of fact, I remember growing up eating lots of fish sticks and macaroni and cheese. That was an easy and inexpensive supper for a single mother working full time while raising three hungry children. I recently came across an old recipe box stuffed with all sorts of magazine and newspaper clippings, yellowed with age and cooking oil. Because her handwriting was barely legible, even to herself, Mother rarely wrote out ingredients and directions. Instead she typed recipes on her old Underwood and, later, on her Smith Corona electric typewriter. In that box, I found one that was a family favorite. Monkey Bread. I can remember the boozy smell of the dough rising as it sat by the wall heater in the family room. Then came the baking, a smell as close to heaven as I’ll ever get. Making Monkey Bread was time consuming. It took patience. And it was a golden gift of love no material possession could hold a candle to. Make some sometime…. (Unless otherwise noted, the Kathryn Tucker Windham blog is written by her daughter, Dilcy Windham Hilley.) Through the years, Mother welcomed a menagerie of visitors into her Selma home. Most of them she knew, but some were total strangers who were simply curious about my mother and/or Jeffrey, our famed resident house ghost. Mother also invited friends and acquaintances often for a bowl of homemade vegetable soup and corn muffins or simply for coffee. Hers was a modest home but one she thoroughly enjoyed sharing with visitors. Some years ago, Selma had a visitor center just off Highway 80 where travelers from all over the world stopped in for information and directions and conversation. “Cap” Swift was, as far as I know, the center’s only personnel. He ran it full time and was a delightful host. He also did not hesitate to give visitors directions to Mother’s house. Sometimes she would return home to find strangers in the front yard photographing her home. But she had a favorite visitor story. She answered a knock at the door one morning to find a group of 10 Asian men standing around in the yard. They were smiling and nodding when Mother appeared. The group spokesman stepped forward and, with a wide grin, inquired, “Open for observation?” In her most gracious Southern manner, Mother discouraged their visit, but she delighted in telling that story time and again. (Unless otherwise noted, the Kathryn Tucker Windham blog is written by her daughter, Dilcy Windham Hilley.) I believe January 14, 1963, was the coldest day in Alabama history. The recent inauguration of Alabama Governor Kay Ivey made me think back on that day. Maybe it wasn’t a record cold day, but it was bitingly bitter. Mother thought it would be a good idea to take my sister, Kitti, and me to Montgomery to see George Wallace sworn in as Alabama’s governor. It was not at all that Mother supported Wallace and his hateful segregationist agenda. Several high school bands were invited to march in the parade, including the Selma band from Parrish High School. Brother Ben played trombone, so we would go cheer on the band while seeing a little democracy in action. Streets leading up to the Capitol were packed with viewers. We were not close enough to hear Wallace’s speech proclaiming “…segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.” It’s fortunate because, had Mother been near, I think she would have belted him with the hefty Alabama State Bible. We were all wrapped up like Ralphie’s little brother in “A Christmas Story.” The wind sliced across our faces, our mouths exposed only to chat with the other parade-goers. The one next to Mother was a tiny, shriveled woman from Jasper who struck up a conversation. When the high school bands came marching by, not a single wind instrument was performing. “I wonder why the horns aren’t playing,” my mother said to our new friend. The little bean of a woman looked at Mother and said, “Lady, it’s too cold to pucker to toot.” That became a much-quoted phrase in my family whenever the weather turned bitterly cold. (Unless otherwise noted, the Kathryn Tucker Windham blog is written by her daughter, Dilcy Windham Hilley.) Ben and I went to Thomasville with a shovel to steal narcissus bulbs. We needed them as a Christmas gift for my 80-year-old mother. She had yearned for bulbs from her mother’s garden for some time, but the owner of the property refused to let her dig just a few. So, brother Ben and I went to steal them. It’s what you do when you love your mother more than life itself and someone dares to tell her no. At the time, Ben was being treated for tongue cancer. He was weak but was determined to come along to assist with the theft. It was twilight when we got to Thomasville. We parked down the road a piece from the house, and stealthily climbed a small hill up into the killjoy’s backyard. And we dug, dropping our plunder into a large grocery sack. We gave the bulbs to my mother for Christmas that year, and she cried. She wrote a little book about it called It’s Christmas. I’m not sure the bulbs ever bloomed, or even that they were narcissus bulbs and not onions. It’s hard to determine those things when you’re stealing in the dark. But I am sure that they were bulbs of some sort from my grandmother’s yard. And I’m pretty sure the spirit of Christmas redeemed us of our sin. (Unless otherwise noted, the Kathryn Tucker Windham blogs are written by her daughter, Dilcy Windham Hilley.)

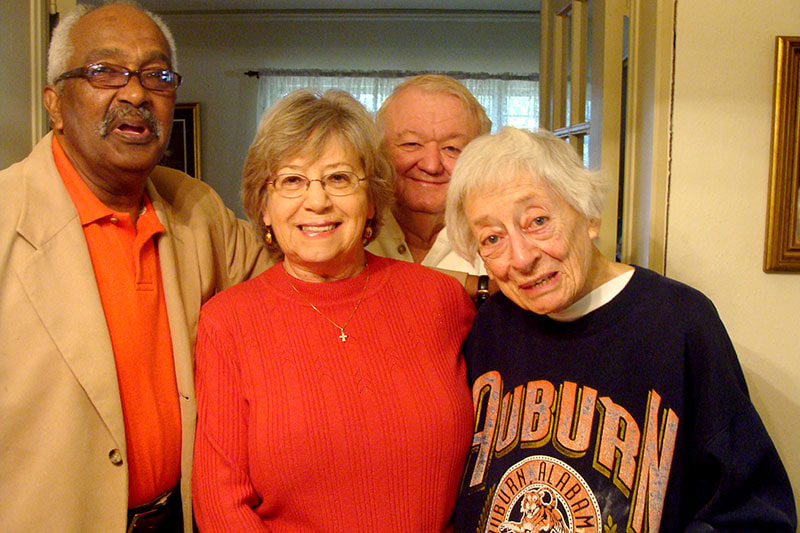

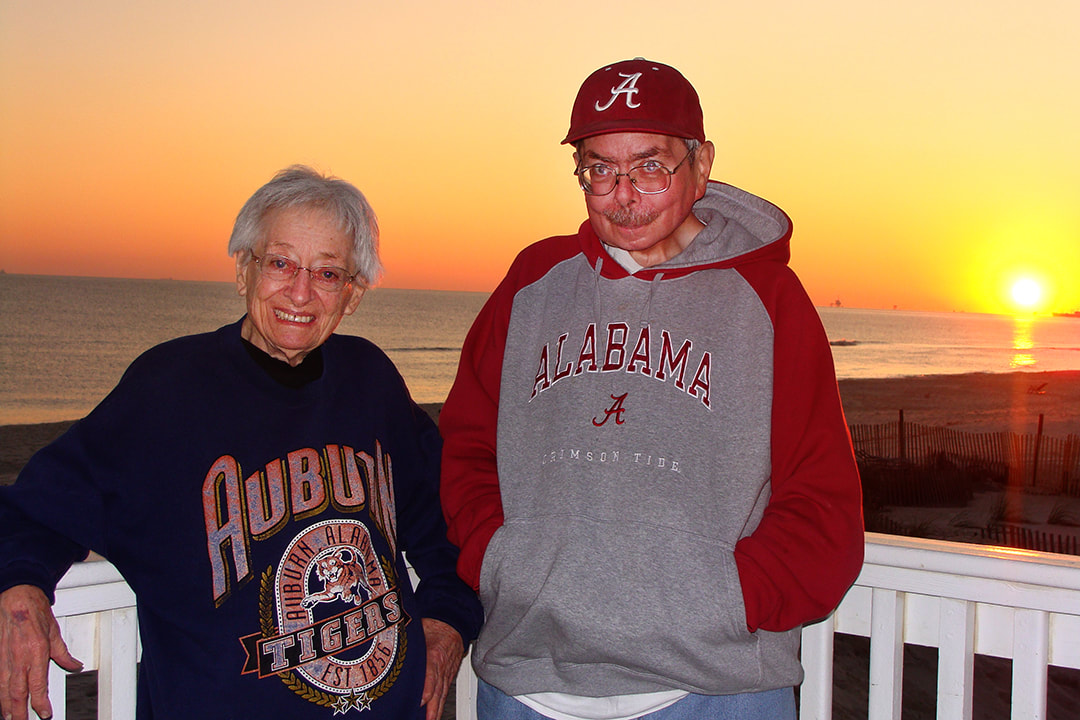

It must have gotten tiresome. For all our growing up years, my mother slept on the sofa by the kitchen the night before Thanksgiving. That way she could get up periodically and “see to the turkey,” basting and such as needed doing. Sometime around 1990, Mother was taken by a brilliant notion. Sometime that September at a family get-together, she announced, “For Thanksgiving I have rented a beach house at Fort Morgan for the week. Anybody who wants to come down for any length of time is welcome to do so.” My brother and sister and I were surprised. What? No more gathering of the family at Mama’s long pine table? No more setting up card tables for the children and overflow guests who inevitably appeared? (For years those guests included the two young men sent to Selma by the Mormon Church in an always-bankrupt attempt to convert somebody…anybody.) We were puzzled, caught off guard, but we recovered quickly. After all, it was the beach. It was a new adventure. It was still a family assemblage, and that’s what mattered. That very first year at the beach, everyone adapted quite well. A roomy house right there on the shores at Ft. Morgan was, after all, something to be really thankful for. And no turkey on earth could hold a candle to the pot of boiling shrimp---huge tasty Reds---that became our traditional Thanksgiving meal. In the early years of the new tradition, Mother would drive down from Selma with my sister, Kitti, on Monday to set up the house for other arrivals later in the week. The rest of us would go down as soon as possible, hording vacation days from work to stretch out the family time at a place that is near perfect in November. In 2005, my sister died just weeks before Thanksgiving. My mother, by then in her 80s, acknowledged her failing eyesight prevented the long drive alone to the beach. But her indomitable spirit insisted on continuing the tradition. “Kitti would want us to go.” That’s all she said. So, every Thanksgiving until Mother’s death, our “adopted” family member, her next door neighbor, Charlie Lucas, would drive with her down on Monday to set up the house. My mother, deeply rooted in her Methodist upbringing, would call all in attendance to gather around the Thanksgiving table. We would hold hands. Mother would say a short and beautiful blessing and make her annual attempt to have each of us say a word of personal thanks. It would begin well. “I’m thankful for each family member and for our friends gathered here today,” I would say. “I give thanks for recovery from the illnesses this family has suffered,” my sister-in-law would say, her words of thanks precious, for there had been many. “Thank you, God, for these people who have taken me in to be part of their loving family,” was Charlie’s prayer. But when it came his turn, my wonderfully irreverent brother would dispel the earnest mood. “Roll Tide!” he’d say, and we’d all collapse into laugher. Even after Mother’s death in 2011, we continued the annual trek to the beach with friends and family for the holiday. This year another Windham has died. This year at Thanksgiving, we will scatter brother Ben’s ashes in the waters at his beloved Fort Morgan. He would want us to. (Unless otherwise noted, the Kathryn Tucker Windham blog is written by her daughter, Dilcy Windham Hilley.)

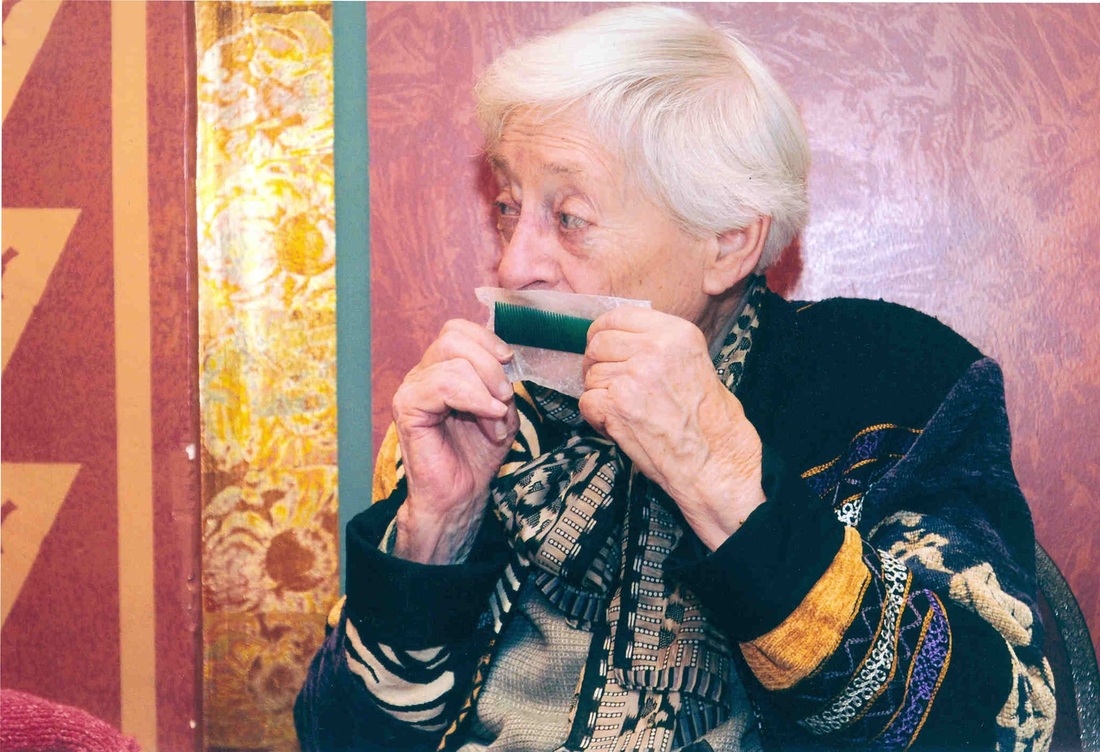

When Mother got really old, she decided to write a book about getting really old. Mother was a prolific writer with more than two dozen books in publication when, at 92, she decided to take on this new subject matter. She’d always written about the places, people and topics she’d known best, and old age was no exception. She said she would write about the burdens and mishaps of having to deal with the visitor that life’s December delivers to your door. She would call it SHE: The Old Woman Who Took Over My Life. As she always did when she wrote, Mother sat at the dining room table with a yellow legal pad and began in longhand. She was not especially well at the time, but she chose to ignore her failing heart and to get on with a project that seemed to energize her. She was in and out of the hospital and physical therapy in those months, but still she wrote. When I went to Selma to visit, she was eager to share new chapters with me. She read aloud to me about her visit to the ophthalmologist who was aghast to learn that Mother had driven herself to his office. She read to me the chapter about repeatedly dialing her prescription number instead of the number for the pharmacy. I cackled out loud about her quest to stay fit by goose stepping through the house while arm-pumping cans of Campbell’s cream of mushroom soup. It was good writing. It was hard work. And then one day it came to an end. Mother was back in the hospital. She’d hit a particularly rough patch, and her spirit was damaged. I went to see about her, and I asked how “SHE” was coming along. “I’ve given up on it,” she told me. “It’s no good.” Mother died within weeks. Her editor and good friend, Randall Williams of NewSouth Books, wouldn’t let the project die with her. By some miraculous turn, he took the barely legible manuscript and pieced it together with pages she had already given him, and he made a book. I wish Mother had lived to see it published. It was on the local bestseller list for weeks and weeks. So many people have told me what joy they’ve gotten from that slender little volume. Now in paperback, it remains a strong seller. It was good. |

Archives

November 2022

We welcome YOUR comments on our blog posts. You will see a "comments" link at the top and bottom of each page. Feel free to join in!

Want to get alerts when new posts are added to this Blog? Visit and "Like" our Facebook page and you will see the new posts there when they are added! Click here to visit the new Kathryn Tucker Windham Facebook Page. |

|

"Some people are important to intellectuals, journalists, or politicians, but Kathryn Tucker Windham is probably the only person I know in Alabama who is important to everybody."

–Wayne Flynt, Professor Emeritus in the Department of History at Auburn University. |

CONTACT US

Dilcy Windham Hilley Email: [email protected] © 2023 - Dilcy Windham Hilley. All rights to images belong to the artists who created them. Site by Mike McCracken [email protected] |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed